- Home

- Tania Szabô

Young, Brave and Beautiful Page 12

Young, Brave and Beautiful Read online

Page 12

Violette was convinced this talk would somehow lead to a new contact. With luck, Denise would be anxious, now that she had got the worst off her chest, to prove her renewed strength and desire to help. Violette was equally anxious; she was still disinclined to believe that Pierre, or even Claude, had given away anything of use to the enemy.

She hoped that describing England, London and the suffering of its citizens, and talking about the man in her life, killed before they could live even a few months of their life together, would bring her and Denise closer together by showing her sincere compassion and understanding, and thus help reinforce Denise’s resolve. She did not mention that he had been a legionnaire and an early member of the Free French Forces under de Gaulle in London, or that she had a daughter.

For her part, Denise’s desire to help Corinne Leroy and undo any wrong she might have perpetrated was growing. As they talked, Denise remarked that Corinne did not have an English accent. She thought Corinne may have come from the Pas-de-Calais or even perhaps Belgium, saying Pierre had a marked English accent.

Violette, laughing, was relieved to hear this. It was a laugh that chimed right to the heart of Denise and made her smile through her drying tears. Violette told her she had worked like the very devil to get rid of any accent. At first she didn’t realise her accent was from the Pas-de-Calais. Perhaps she should have known, as she had spent a large part of her childhood in the area, and many holidays since.

In the streets below were the afternoon sounds of people talking, sometimes laughing, sometimes yelling in argument. Every now and then, the women could hear, through the general daytime murmur, individual shouts and the screech of tyres as military vehicles hurtled up and down. There were very few private cars and most of those were old jalopies running on God-knew-what, known as gazogènes.51 The sounds mingled in a steady background buzz as the two women began to strike up what could become a lasting friendship, if trust could be firmly established.

Although the age difference was a good decade, it seemed not to matter. Violette, mature and self-contained for her years, could make Denise laugh a little. Her lively nature bubbled under the surface and, on this, her first vital visit, broke through just often enough to soothe and beguile her older companion. Violette recognised that Madame Desvaux had a wealth of experience to pass on to her and that she was an intelligent if not exceptionally strong-willed woman.

‘Let me suggest something to you, Corinne,’ Madame Desvaux proposed. ‘I think it would be much safer if you came to stay with me. We can easily explain, if we have to, that I’m an old friend of the family and bumped into you in the street. You could tell the patronne of the guesthouse, Madame Thivier, that you’ve met up with a family friend who invited you to stay. Try not to give her the name or address so that your whereabouts in Rouen remains unknown or at least elusive.’

‘But you would be putting yourself in great danger again, madame,’ protested Violette. Also, it could be a trap, although she did not think so.

‘I’m used to that now and, anyway, a bomb could come and do the job anytime. And I would be delighted to have a little company for a while. Please do accept. I will sleep easier, knowing that you are relatively safe under my roof.’

The apartment had three or four good sized bedrooms along the wide halls. Although looking somewhat the worse for wear, it was a well-furnished apartment, comfortable, with lots of space. All of which could give a false sense of security, an extremely dangerous state of mind. Violette would feel very safe here if she were just a little surer of the loyalty of the lady of the house, or if she knew that the house and its occupant were not under constant or partial surveillance. Would she really be safe here?

‘I don’t know how to thank you for such a kind and brave offer. But I think I should stay in the guesthouse as I’m established there. If I check out now before leaving town, I would draw unnecessary attention to myself. That’s not good, is it? And I would not like to put you in unnecessary danger. It is so very kind of you, though. But maybe you can help in another way. My job is to meet as many of Charles’s circuit members as I can to see who has escaped the clutches of the Germans and what, if anything, can be resurrected or planned. Can you help me in this?’

She hoped that mentioning Philippe and his circuit again remind Denise of her reason for being in Rouen, and that time was of the essence.

‘You’re very wise, Corinne, for such a young person.’ said Madame Desvaux. ‘On reflection, I think you’re quite right. However, you will join me for lunch here tomorrow, won’t you? I’d like to think about how I might be able to help. It will indeed be difficult. Terrible things have happened in the last months, and I will tell you more about them tomorrow. I won’t suggest dinner because of curfew. Lunch tomorrow. Around one o’clock, would that suit you?’ There was no hesitation in Violette’s response although her heart contracted a little at the thought of the possible danger of coming back here to a waiting Gestapo ambush.

‘Perfect. I’d better leave now to have a bit of a look around and familiarise myself with the town generally. If anything crops up, you could leave a vague message at the guesthouse. If you mention a piece of orange clothing or a scarf, not red, it will mean “danger” and blue, not green, will mean “be careful but no obvious danger”.’

‘Good thinking. And be prudent, child, as you walk the streets. Put your scarf back on your head. You are very beautiful and the scarf makes you less noticeable. Au revoir until tomorrow, then, petite.’

‘Thank you, à bientôt!’ Violette pulled her scarf tightly round her head and tied it under her chin. As Madame Desvaux closed the door behind her, she walked along the corridor and down the stairs, relieved not to have bumped into anyone, and reached the entrance. Taking a deep breath, she stepped outside.

‡

* * *

50 Compulsory work service – Service de travail obligatoire (STO) was initiated by the Pétainist government by law on 26 February 1943. It had the effect of making those young men and their families and friends the enemies of the government. The men went into hiding and the Maquis was born; their families and friends became the nascent Résistance.

51 Gazogènes were vehicles produced in France fuelled by burning wood and other vegetable-based materials. They enabled the French with or without vehicular and travelling permits to still run trucks, cars and motorbikes.

9

Dubito Ergo Sum

Tuesday 11 April 1944

Dubito, ergo sum

I doubt, therefore I survive

The motto of many of SOE F section’s best men and women,

d’après René Descartes

Violette was not keen to step outside into danger again, but it was her job. So she walked resolutely back to the relative safety of her hotel. Her jangled nerves were beginning to settle after her encounter with Madame Desvaux, but her feet were beginning to object to being made to walk over cobbles and more cobbles, no matter how well laid and smooth they were.

She would drop into a café-bar where she could put her thoughts in order while meditating over a late lunch. A strange feeling of unreality invaded her. Except for those with bomb damage, most of the streets at first glance looked the same as streets in any French town. She had walked along the quays, passing a parade of German troops, and turned into rue Grand-Pont. At the crossroad with the small rue du Petit Salut she noticed ahead that pedestrians were being halted and taken aside to be checked by a group of young Doriotistes, who were effectively a bunch of French Nazi thugs, liking nothing more than to bully and put fear into their compatriots. It was from this group of fanatical right-wingers that the Milice had emerged the year before, but the Milice had the huge advantage of real and overwhelming political clout, and they used it on a whim to inflict hurt and terror.

Heart suddenly thumping, Violette quickly turned left into a small lane and walked hurriedly into rue du Bac. As she came onto rue de la Pie she saw long queues of people waiting to get hold of a few

clothes from the tailor’s shop and food from the grocer’s shop next door. Everyone there looked scruffy, worn out and resigned. The tailor’s shop window was blown, the feeble protection of hanging brown paper was torn, leaving a gaping black hole. An iron guardrail had been added across the shop fronts to a height of about two metres, to prevent looting and help control unruly queues.

A little way along, Violette noticed a printer’s shop by the name of Wolf and made a mental note of it. She recalled that she had heard the name before, probably at one of the planning meetings for her mission. There were unsightly notices of German Ordnungen posted on windows, doors or hanging from makeshift posts: orders designed to control the population, to insist on compliance, sometimes on pain of death by firing squad.

The Hôtel de Ville had huge red, black and white banner swastikas hanging from roof level. As she walked along the opposite side of the large square, Violette saw the shops reduced to scruffy exteriors with empty shelves that had previously been piled with essential or luxury goods. Windows were cracked, empty or covered in cardboard announcements stuck on at odd angles. Many shops, all over the town, looked shut or abandoned. There were queues for bread and other essentials. She watched a number of disputes burst out about who was next, or just how many ration points were needed. She passed five street checks in as many minutes.

The clouds skittered above her in the stiff breeze. Violette felt utterly alone; she was alert and very tense at the thought that an officer might demand to check her papers again. Had Madame Desvaux walked round to the Milice or police and reported her? She repeatedly checked covertly to see if she was being followed and felt just a little paranoid. She decided to treat her movements about town exactly like her exercises under SOE training – like a game.

Violette felt that the visit to Madame Desvaux had been worthwhile as a starting point, even if it had scared her. After those first uneasy fifteen minutes or so, they had warmed to one another, at least superficially. By the exchange of what was relatively inconsequential but emotionally charged information (mostly already known to Violette), they had begun, it seemed, to establish a certain level of trust. If not, she would soon be disabused of that idea. Denise held all the cards and Violette felt uncomfortable at the thought of being entirely in her hands.

She felt safe enough in the guesthouse for the time being, but maybe it would be prudent to have a bolthole. After all, she could create the cover of staying with a friend while looking for her fictitious uncle, or persuade someone to act as her lover and supply her with lodgings for a while. She could, at a pinch, contact ‘her’ Wehrmacht colonel, Colonel Niederholen.

Even if Madame Desvaux turned out to be as determined as she seemed to help the Allied cause, Violette surmised that staying at her apartment would be entirely inappropriate as the woman had already had a ‘nephew’ staying on to help her. Violette was sure it would be unusual and therefore remarked upon by neighbours if Denise should have another relative or friend to stay just a few short weeks after the first had left.

A small café-bar beckoned in a tiny side street on the way to her hotel. The plat du jour was a simple but tasty dish of beans and small chunks of bacon. Beans were in good supply most of the time but meat was rare; there was just sufficient bacon to give a little taste to the beans. There was also bread of the ‘national’ kind. While Violette ate, she pondered again the danger of staying too long at the hotel. It might be possible, she thought, to find another safe-house. She would mention that tomorrow at lunch with Madame Desvaux.

‡

While she was eating, two German soldiers came in, sat at a neighbouring table and smiled broadly in her direction, trying to catch her eye and engage her in conversation. She ignored them, forcing herself to continue eating even though her stomach clenched tight. Trying not to hurry, she finished her meal and settled her bill using her forged ration cards. She opened the door and walked out, heart thumping, trusting they would not follow her as they were only halfway through their meal. She remembered Denise’s advice and quickly pulled the scarf tight round her head and retied the knot under her chin. She walked rapidly and with purpose towards the protection of her hotel room.

What a relief to see her guesthouse at the end of the next street. She would ensconce herself in her room for the evening. She had already stopped at a little tabac, bought a magazine, a newspaper and a French historical romance; these fitted her cover as a young commercial secretary and would also help to refresh her idiomatic French. She had also purchased food to eat later that night in her room while reading. She would ask the patronne if she could have some fresh coffee brought up during the evening.

As she entered the hotel, she heard herself being called urgently over to the reception desk where Madame Thivier handed over a package that had been delivered for Violette. She surreptiously whispered to Violette to be very careful with all that she was doing and the people she was visiting.

Violette thanked her for her concern assuring her that she was being very careful. Then, as she felt a little drained, she asked for some coffee or hot chocolate to be brought up to her room a little later to which the patronne said it would be her pleasure in about half an hour, smiling anxiously as she watched Violette climb the stairs to her room

Violette read the note as she walked along, noticed the word blue and remembered she had asked Denise to use that colour if everything was reasonably safe. That was certainly a good start. She opened the package to find a cardigan with instructions to take it first thing in the morning to the boutique managed by the Monsieur and Madame Sueur. Violette had looked forward to meeting Florentine Sueur who was imprisoned and now it would be her assistant, Lise Valois, whom she saw. Things were slowly moving forward – at last. With luck, the pace could pick up in the next day or so, if she gained the confidence of these two women.

‡

Violette had a hot bath and afterwards stretched out on the bed as the last rays of the setting sun streamed through the window. Madame Thivier brought in a tray of steaming dark chocolate and cake. Violette thanked her, and after the door closed started to read the newspapers, especially the advertisements showing her where and what various businesses there were – boutiques, florists, grocers, garages, cinemas, cafés-théâtres, cafés and the plethora of small businesses that towns of any size contain. There were many German and Vichy advertisements and notices warning people about official orders, new regulations and certain goods that would be restricted. She could not help but giggle aloud when she read a German notice ordering the population to use the pavements correctly, that they must walk on the left and pass on the right! Never push past a German – soldier or civilian – but always show deference – under threat of a fine.

For a while, Violette read her historical romance then, concentrating, went over her plans. It was hard to know where to begin. She went over the list of names and activities that she had memorised in London, and the reports and debriefings that she had read and reread. As she considered her meeting with Madame Desvaux she realised she had made a few significant discoveries helpful to piecing together the disintegration of this successful circuit. From Madame Desvaux’s account, Isidore had been arrested at her residence. She and Isidore had had an ongoing sentimental and physical relationship up to the time of his arrest. The shock of the arrest had been great and Denise was a very frightened woman. Her actions manifestly showed that she should no longer be trusted. And yet … and yet … Tomorrow would shed more light on Madame Desvaux and the arrest of Isidore. Denise’s trustworthiness worried Violette greatly but for now she needed to push it to the back of her mind.

She returned to going over the background information she had received in London. Philippe had been in Rouen since April last year. Philippe and Isidore had over the months met quite openly and frequently, mostly at the Brasserie Marigold in place des Emmurées on the left bank. Since December, Philippe and Bob Maloubier had been on the run from the enemy, along with four other agents from other c

ircuits, putting Henri Déricourt’s safe-houses in danger through overuse during the terrible winter weather of 1943. Philippe had been ordered to withdraw; this was probably due to the increasing number of round-ups perpetrated by the Gestapo now that the Germans’ attention had been galvanised by the stream of sabotage carried out by his Salesman circuit from June 1943. She wondered whether this could be evidence of a much wider net being cast by the Gestapo, not only over SOE circuits but also over de Gaulle’s movements and circuits, and those of British SIS (MI6) and others. She would try to discover whether there could be any basis in fact to her conjectures.

Philippe had reported on his return to London that the Germans had made just one attempt to penetrate his circuit but Violette believed it was more likely that they had not only penetrated circuits, including Salesman, but also had informers inside the circuits. It would not be possible, Philippe had told her in London, to rely on his contacts in the Rouen police for much longer, although they had been efficient in the past in warning him of arrests in the offing.

She had studied very carefully the garbled message received in London from the Author circuit, situated far south of Rouen in the Corrèze, ran by Harry Peulevé, Violette’s close friend, under the alias of Jean. André Malraux and his FTP52 group had been in touch with Harry and, although up to this time Malraux had not been too involved in the war, after the death of his half-brother, Roland, an important member of Harry’s circuit, he put aside most of his writing and involved himself in what seemed to some French historians as somewhat bizarre ways – for example, in calling himself Colonel Berger, when he had no military standing whatsoever. This taking on or bestowing of temporary military titles was not unusual among the many factions, groups and sub-groups of the Maquis and semi-military Résistance in France and, of course, SOE. Philippe was a French journalist and yet held the British temporary rank of major,53 Major Charles Staunton, and Violette was a lieutenant in FANY (ATS). André Malraux was attached to de Gaulle’s networks, not SOE’s, entrusted with uniting the various factions, of which there were many, under one umbrella – an unenviable task yet essential to prevent the country falling into chaos after liberation. Violette mused that the cells were not all self-contained and contact between them was not perhaps as secure as one would wish.

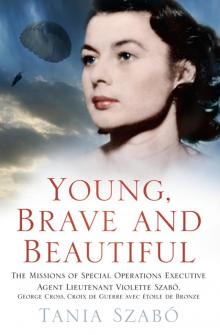

Young, Brave and Beautiful

Young, Brave and Beautiful