- Home

- Tania Szabô

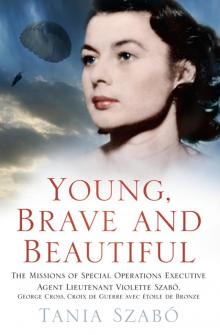

Young, Brave and Beautiful Page 10

Young, Brave and Beautiful Read online

Page 10

The block of apartments containing number 12 was still standing amid the rubble of one or two surrounding buildings, its walls bearing the scars of war. There were large cracks and nearly all the glass in the windows was missing or had slivers edging the window frames. Glass had been replaced by blackout paper, boards or thick curtains drawn across. The pervasive but dying stench of old fires and rubble was strong as Violette walked along slowly, noting these details.

She was feeling extremely uneasy and tense in this terrible expanse of destruction, surrounded by a fully armed and tetchy enemy and by those who collaborated. She walked towards where an old man was sitting on a crooked pile of bricks and rubble, picking through some strewn bits and pieces of what must have been his home; tears had made rivulets down his dust-covered cheeks. On getting closer, Violette saw that he was not an old man, probably not more than forty. His grubby and shredded clothes, shoulders hunched forward, spare bony body and the deep weariness and desolate sadness of his eyes made him appear years older.

A woman, head covered in a shawl, scurried past with a child of about seven at her side. She looked at Violette suspiciously as she hurried past, making Violette aware that she must make her own clothes look more worn and tired looking. She let her shoes scuff along for a few steps in the dust as the first step in creating a look more in keeping with her new surroundings. Then she bent as if to pull something from the rubble, let her hands drift in the dust and stood back up brushing her clothes down with those now dusty hands, as if straightening them. This left a few patches of dust smearing her light coat. Then she rubbed them down to clean off the excess, thus leaving the inevitable dust stains that appeared on the clothing of most of the people in the streets of Rouen.

‡

Finally, Violette warily stepped into the concierge’s office in the apartment building. It was empty but she found Madame Desvaux’s name on a pigeonhole, walked up the two floors and knocked. A woman of forty-something came out quickly and asked: ‘What do you want?’

‘I’m looking for a friend of mine; he’s living with his aunt, a Madame Desvaux. I wonder if you would be his aunt, as this is the number of the flat he gave me, or would you know where I could find them? I understand she makes beautiful clothes and does extremely professional repair work.’

‘Mademoiselle, that may well be true. But he’s not here and I’m very busy,’ the woman replied, wondering why this girl was asking about her nephew. It’s been two months since Pierre was arrested, she thought to herself, and this morning I heard he was being deported via Compiègne. When this was his safe-house the cover story was that he was my nephew, helping me in my business. Could she possibly mean him?

‘Actually,’ said Violette, hesitating a little, while she gathered her thoughts. ‘He said I might ask if you repair knitted garments.’

She involuntarily shivered; the wide hall was cold and dark and her light summer coat was not heavy enough to keep out the chill of this old but elegant maison. Private dwellings were forbidden to use any form of central heating. Even electricity and gas for lighting and cooking were severely rationed, sometimes limited to as little as one hour a day.

‘Oh,’ sighed the woman, clearly scared. ‘I don’t know if I can help, but do come inside – you look chilled to the bone.’ She looked anxiously up and down the corridor. ‘Yes, I can do most repairs on knitwear; it just depends on what you want done. I’d need to see the garment. Come on – come in!’

This last seemed to be said to satisfy the curiosity of a woman walking up the stairs at the end of the corridor. She nodded amiably enough in greeting to the two women and continued her climb to the next floor.

Within this brief conversation of introduction, Violette and Madame Desvaux had also exchanged a coded signal of recognition. The mention of the knitted garment was intended to establish Violette’s bona fides.

Once inside, Madame Desvaux walked towards the kitchen. ‘You could do with some coffee, I should think. You’re doing something very dangerous, you know. You could get yourself, and me, into serious difficulty and probably worse.’

‘Yes, I know, madame. Could you please confirm your name?’ Violette stayed just inside the door for the moment; she had learned in her training the usefulness of some basic questioning techniques, such as the unexpected stance she now took.

‘Mais oui, je suis certainement Madame Denise Desvaux.,’ the woman replied, a little taken aback.

‘Thank you, Madame Desvaux. I’m Corinne Leroy. I had to ask, you see, as I’ve been sent by Charles to discover what has happened to his network. Is Pierre, to whom you so bravely gave shelter, still living here? Charles and our people are extremely worried about what has happened to his circuit and to Pierre. We received a very strange message and my masters have sent me to discover the extent of the damage to Charles’s circuit. We’d heard Pierre had probably been arrested.’

‘Oh, my goodness. You don’t know the half of it. It was utterly terrifying and my poor Pierre, I don’t know what will happen to him. I was arrested and interrogated over a whole week. After that, I went to see him, Cicero42 and Jean and Florentine Sueur once a week. When I was told it was for the last time I thought they were going to shoot them. But no, they’re to be sent to Germany tomorrow. Pierre is such a lovely man. We became very close over the nine months he was with me. I pray every day that he’ll survive.’ She took out a handkerchief and wiped her weeping eyes. ‘You know, you’re lucky I got back early. I go to Madame Sueur’s shop with the clothes I’ve finished after I’ve visited Pierre, Cicero, Jean and Florentine – they’re in the same cell, you know. Not Jean, but Cicero and Pierre. But today, after hearing they’re to be deported, I was just too upset to go anywhere.’

‘Could you tell me what happened?’ asked Violette in a diffident manner. She did not wish to seem to interrogate Denise. The woman was upset and frightened. She was attractive, slim and well dressed, although her clothes were old.

Violette was alarmed by what she had just heard. Not only Isidore, but also Philippe’s boîte aux lettres, Jean43 and Philippe’s lieutenant, Claude Malraux, had been seized. This confirmed the message radioed to London in March, but the blow was no less terrible: Philippe had necessarily informed Claude Malraux of all he knew and plans for the Salesman circuit so that Claude could take full charge after Philippe had been recalled to London in February.

‘Asseyez-vous, Mademoiselle, je vous prie!’Madame Desvaux gestured towards a chair at the kitchen table while she made coffee. As she sat down, Violette felt strangely at home, strongly reminded of her last visit to Tante Marguerite. She looked at all the familiar objects and fleetingly felt happy; nevertheless she remained extremely tense. The news was disastrous, and poor Madame Desvaux did not seem at all pleased to see her. And who could wonder at that? It was very dangerous.

‘You could have been followed, you know, mademoiselle.’

‘No, madame, I have been extremely careful and made a number of detours as I made my way here. Definitely, I was not followed.’ She continued softly, ‘I wonder if you would be willing to help me in any way at all? I realise how dangerous it is for you, but we are getting so close to winning this war and bringing all the destruction, privations and fear to an end. The people here have been superb, what with all the sabotage they’ve carried out over the last four years, and information they’ve passed to London. My mission is to discover what has happened to everyone and see what London or I can do to help, and to see if we can resuscitate the network. I’m here to help in any way I can and have certain instructions to pass on. I can give financial help to the families left without an adequate breadwinner. There must have been some treachery somewhere, mustn’t there?’ commented Violette briefly, and then continued quickly without waiting for a reply. ‘Charles has sent me, and given me carte blanche to do whatever might be required and to assist wherever possible.’

Charles Beauchamp was the name Philippe used in certain parts of Rouen and for which he held ident

ity papers, and Clément Beauchamp in others. He, as did Violette, held the all-important German-stamped passes for the zone interdite. Anyone anywhere in this zone without a pass bearing German stamps would be arrested and questioned.

‘Well,’ said Madame Desvaux, softening a little, ‘I’m afraid the news is not at all encouraging. So many have been taken in for questioning, arrested, tortured, deported and, in too many cases, shot. Including the two who held the weapons dumps – that’s Jo and Chevallier. It has been a dreadful time. Our whole network, it seems, has been destroyed. There are only a handful of people left and they’re now perhaps too afraid to do anything. Not just afraid for themselves, but also for their families and friends.’ Tears welled up again but were contained. She went on to describe some of the events and prevailing sentiments: ‘And then, to top it all, the Allies bombed us, so we’re all feeling pretty dispirited. Thank God the bombs have mainly fallen on specific targets: the gas works and the like, but as you can see in my own street, we’ve been pretty badly hit, all the same.’

‘Yes, I know,’ said Violette, quickly thinking how she might gain the other woman’s confidence. ‘It’s been just like that in London, but at least we know it’s only from the enemy. For you people of France it’s even worse. You have to suffer bombing, too, not only from the enemy but also from your allies; plus you are living under the guns and interrogations of hostile invaders. It must all make everything particularly difficult and confusing, too.’

‘Yes.’ She smiled at Violette’s sympathetic gaze. ‘Have some more coffee – it’s almost real coffee. I add just a little chicory to make it go further as I don’t know when I’ll be able to get any more.44 And the sugar’s black market; Pierre got me a huge brown paper bag full!’ She stifled a sob at the thought of his being deported today to Germany to God only knew what fate.

‘Thank you very much.’ Violette added: ‘I shall replace the coffee for you as I have a packet hidden in my suitcase at the little hotel where I’m staying.’

‘Are you sure your hotel is safe? The Abwehr, the Gestapo, the Milice, especially that salaud45 Chief Inspector Alie, and even the ordinary police sometimes, all make a particular effort to check the register of hotels and guest houses and the identity papers and zone passes of the guests. When they find anyone suspected of being involved in clandestine activities, they’re particularly brutal.’ She looked carefully at Violette and asked: ‘Can’t you find a safe-house to stay in? Haven’t you seen the notice in the hotel hall ordering everyone to have identity cards, permis de séjour or other permissions for just about everything?’

‘Well, I can’t be absolutely sure of the hotel. It’s in rue Saint-Romain. The patronne, Madame Thivier, has been very kind so far and seems to dislike the Germans. It’s the small private hotel just north of the bombed Halle aux Toiles and two steps from the cathedral.’

‘Ah, if it’s the one I think it is, I know her just a little. A friend of mine said how angry she had been a few months ago at the Germans bullying their way around and asking all kinds of impertinent questions about her guests. She gave them a hard time, it seems. And still does. I think you’re safe there, at least for the moment.’

Violette decided that this woman was brave to have put her life in danger by housing Pierre, and she was being very hospitable. But still, this visit could prove disastrous, even fatal to her if Madame Desvaux were not what she seemed and decided to report her to the enemy authorities.

Madame Desvaux poured the coffee and carefully assessed her visitor. She was taking to this discreet young woman who had come knocking so unexpectedly at her door. She must have had a dangerous journey from England. She knew she had to tell Violette everything that had happened on 9 March, just one month ago, and her own unfortunate reaction.

Madame Desvaux explained how Isidore (Pierre) had used fifty-four different locations with at times as much as forty miles distance between them for sending clandestine messages to and receiving them from London. She described how he had lived with her since mid-July 1943 and they had become lovers, in spite of his younger age, and held one another in genuine affection. Therefore, she knew more, perhaps, than she ought. Colin Gubbins, head of SOE, later wrote in the citation for Isidore’s MBE that he worked untiringly in an area thick with enemy troops and Gestapo, making possible the delivery of arms to his circuit on a large scale. On this mission, Isidore had sent fifty-four messages to London.46 How on earth had he done it and survived for so long? Violette knew it was careful security procedures and tenacious courage that had made it possible. She had been told in London that he always took elaborate precautions and followed every security rule available to him. She remembered he had been the wireless operator for Odette and Captain Peter Churchill47 but left, refusing to send over-long and unnecessary messages to London for one of Peter’s men. Isidore considered such behaviour a huge and unnecessary security risk. At the beginning of March 1944, Isidore had stopped sending messages after nearly eight months of steady contact. Had his radio been detected by a German listening van?

When Philippe slipped out of Rouen in November 1943, coming back once or twice before his return to England had been arranged by Lysander in early February 1944, he had put Claude Malraux, his second-in-command, or his lieutenant, as he preferred to refer to those he had placed in such positions, firmly in charge – divulging to him all the important details of the Salesman circuit, including weapons dumps and letter drops – those people trusted to receive clandestine visitors and verbal, even occasionally written, messages; people like Georges Philippon (Jo) and Jean Sueur, the staunch Gaullist and respected external member of the very secretive group Violette hoped to contact.

Madame Desvaux went on to say that she knew that Claude had been a worried man who clearly did not know quite what to do. Claude and his partner48 met Madame Desvaux and Isidore socially from time to time, usually in a restaurant or sometimes in one of their homes. She said that Claude seemed preoccupied, as if he knew something was afoot but was powerless to take action.

Claude had told Pierre that the main arms and explosives dump at Philippon’s garage had been raided by the Gestapo. He had gone on to explain that the Gestapo had seized the five-ton truck that Philippe had used to transport arms; information which Violette knew Pierre had transmitted to London.

Violette asked when Cicero had told all this to Pierre. Madame Desvaux said that on 7 March, two days before they were all arrested that they decided to have dinner at her place on 9 March, a Thursday, so that they could discuss what they should do. She reiterated that Cicero seemed listless and incapable of making decisions or taking action.

At the memory tears welled up again but were held back.

Denise really did not know what to think as both Pierre and herself did not know if it was through sheer lack of nerve or because Cicero was expecting Charles to return that he took no action.

Violette thought that it was probably a bit of both: but privately that Claude waiting for Philippe’s imminent return was pure procrastination. She thought if she or Philippe had been there, they would have immediately sent Georges Philippon, his wife, Jean and Florentine Sueur, plus Philippon’s close friend Chevallier with his wife, into hiding for the duration of the war. This may have meant sacrificing any further contributions those people could have made, but it might have saved half the organisation. She surmised correctly that the usefulness of this group of people had probably reached an end and so they should have been protected at once. It was clear that instead the violent loss of these people was a crippling blow, especially to the internal arrangements of the rest of the organisation and the ongoing preparations for the Allied landings.

Madame Desvaux broke into Violette’s thoughts with the news that Georges Philippon and Chevallier were shot on 12 March, three days after the Gestapo came for them all. The thought that it was because of the rest of them that they were arrested and shot was simply too awful to contemplate. Denise could not recall any of them mention

ing their names. She said she certainly had not but then it was impossible for her to believe that Pierre had, either there or in prison, and surely Cicero had not given anything away. However, under interrogation and Denise thought especially fears for one’s family, one just never knew. At least Pierre did not have that problem.

Madame Desvaux told Violette that Pierre had gone out very early on 8 March to meet his bodyguard and wireless operator, Broni, so they could transmit together as Broni had messages to send to London from his own groups. He had asked Denise to meet Broni a little earlier and take him to their agreed meeting place. Pierre would go there by a separate route. Pierre and Broni had been good friends, going everywhere together. They were certainly not an uncommon sight and it was generally believed, encouraged by the two men, that they were involved in the black market. So, Violette concluded as Denise continued her narrative, Pierre must have had some serious concerns otherwise he would not have suggested such a devious plan for their meeting. Violette hoped he had told Broni to find himself a safe-house and keep out of sight for a while. Pierre had returned in the late afternoon, continued Denise. He did not seem unduly stressed, or particularly concerned. Denise asked him if he had put his wireless set and crystals in their hiding place, but he told her that Broni needed them as he had many messages to send for his group. He’d get them back tomorrow or the day after, he said, when they next met.

Poor Broni did not have the slightest chance to escape. Later, on 11 March, he was cornered by the Gestapo in his own home with his brother Felix who, having grabbed his pistol, was shot dead. It was absolutely typical of Felix to resist arrest. However, Broni was captured and taken away. After being badly tortured, he was sent first to Auschwitz, then Buchenwald, and finally Bora but miraculously survived.49

Young, Brave and Beautiful

Young, Brave and Beautiful