- Home

- Tania Szabô

Young, Brave and Beautiful Page 9

Young, Brave and Beautiful Read online

Page 9

‘He certainly gives that impression,’ said Harry, ‘but you know, I don’t believe it for a minute. I’ve seen him in relaxed mood. Then, he shows another side. And he’s not the best organised of men – that’s why Vera Atkins is always close by. She’s a bit of a stickler for detail and follows up every single loose end that Buckmaster leaves trailing, making sure it’s tied fast. Marvellous, she is, really. Just like you. You’re just too adorable for words and I love you, I really do. After this is all over, we’ll sit down and talk, won’t we, Vi?’

‘Yes, for sure, Harry. Anyhow, we shouldn’t be talking about these things here. Keep mum – haven’t you seen the signs?’

Harry was smitten with Violette. She was very fond of him too and always greatly enjoyed spending time with him. He was tall and handsome and had something of the eternal child about him. She was still too angry and sad over the life with Étienne that had been snatched from her to make any commitment. It was strange it was war that had brought them together in the first place for their hauntingly sweet and short-lived love affair. Her imagination had sparkled and soared at the dreams of a life shared with her gallant legionnaire, full of vitality and laughter. They would have had an active and adventurous life in the south of France after the years of war, with her travelling to exotic destinations as a legionnaire’s wife for a few years and then he would have retired as a French officer and with French nationality merited, as they said, through blood shed for his adopted country. Violette had looked forward so much to the life they would build together. But it was not to be; he was gone.

She still got on with life, and she and Harry had been out together many times, dancing in the popular dance halls, to the local pubs and the cinema. Life went on, but the sadness remained deep in her glorious eyes.

Violette and Harry had both been trained by SOE. Harry had already been sent to France, where he’d broken his leg; he had come back and, after further training, asked to be sent again so he could achieve something. Violette was just about to be sent. When they had first met in 1943 at one of the clubs like the Studio Club, he was under the impression that she knew nothing about his clandestine work. He did not realise how savvy she was. She knew he was ‘up to tricks’ in France in the same way she had learned to spot other men who were agents. She reflected once that it was infinitely more difficult to spot the women, even after spending some time in their company. She thought that women attracted to this sort of work revelled in the fact that they were involved in something secret and confidential. She did and her mother along with Tante Marguerite typified the woman who could hold her own counsel at all times and did.

‡

Violette finally left the café-bar and wandered the quieter lanes and streets, where sometimes there was not a German in sight. She found the peace of these small cobbled alleyways and streets helpful in sorting out what to do first. She decided to collect her luggage immediately and find a small private hotel choosing one in a small street, rue Saint-Romain, a short walk from the station in the north and the destroyed Pont Corneille to the south.

As she entered the hotel, she remarked to the patronne, ‘C’est beaucoup de dégâts, non?’ gesturing towards the damage in the town.

‘Epouvantable, épouvantable,’38 wailed the owner, Madame Thivier, a woman in her late fifties who looked closer to seventy, as she glanced out at the dreadful damage across the small square. Madame Thivier explained how lucky they were not to have been hit as so many had been killed by the Allies and it really made you wonder whose side to be on when such damage was done by friends.

Violette nodded and asked if there was a room for a few nights to which Madame Thivier offered one right next to the bathroom and asked if that would suit. Violette thought that perfect and revelled in the idea of a bath after her long and stressful journey. The patronne agreed, warning that each bath would cost a little extra but if Violette did not mind that she would be entitled to one bath a day, perhaps not with hot water but that she did her best regardless of Boche restrictions.

Violette thanked her hostess adding after noting the comment about the Boches that it must have been dreadful having all those enemy soldiers marching by each day in those lovely old lanes. She asked if many came there to stay while she was trying to decide whether this seemingly elderly, tired-looking woman was a collabo or not.

Madame Thivier replied adamantly in the negative. She said that they were either in their barracks or officers who stayed in luxury hotels or requisitioned houses as it pleased them. She went on that they did do a lot of stamping about, though, marching here and marching there, checking people’s papers every few seconds. She felt it was degrading, utterly degrading and then her eyes narrowed as she hoped her new guest was not some busybody informer. She was suddenly afraid and suspicious, knowing she did not know how to hold her own tongue.

‘No, just passing through,’ Violette reassured her with a warm smile, explaining that she was just passing through having been in Paris for Easter. She explained that in a few days she would have to go home to Le Havre and was afraid of what she might find there. Carefully checking for Madame Thivier’s reaction she continued that it was a terrible war and the sooner peace was declared the better. She had carefully controlled her accent, watching surreptitiously for the woman’s reaction. None. Now that was a relief!

As Madame Thivier took Violette up to her room at her request, she explained that she had the prettiest room overlooking the courtyard and that breakfast was served downstairs from seven in the morning until eight thirty. Chatting casually, Violette asked where she might go that evening for dinner.

Madame Thivier eagerly suggested a little café-bar two streets away that would do nicely – cheap, clean, good local food and decent folk. Not many Germans went there as it was out of the way. She offered Violette an umbrella if she needed it.

Violette thanked her politely feeling more comfortable with her hostess as they descended the stairs. She accepted the room and offered her papers as the fiche was filled in. She went up to her room and unpacked.

She luxuriated in a hot bath, ridding herself of the dust of travel and the smell of sweat from her fellow travellers. For the next few hours Violette stayed in her room, which was basic but comfortable. A blue flowered china jug of water stood in its matching basin. She had already hung up her few clothes, putting her underwear in a drawer. It was a nice room and she felt reasonably secure. She hoped the woman was who she seemed, and not a canny informant. She lay down on the bed, relaxed and thought what she ought to do the next day.

Looking out of the window on to the courtyard, she saw that there were chickens in a run and a few rabbits in hutches. Vines and other plants grew in tubs and buckets: a veritable pantry of fresh fare. There was a gate into the yard that seemed to open out on to an alleyway.

It did rain, and hard. When it stopped, Violette ventured out to the estaminet recommended by the patronne, Madame Thivier, taking the offered umbrella with her against further showers. As she was feeling a little drained from the excitement of the day, she felt she would eat quickly and return to rest. She found a table in a corner and, after quietly ordering her meal, watched who came and went and who spoke to whom, wondering if there would be a friendly face. Each person cast a glance in her direction but to her relief made no move to strike up conversation. She ate a simple meal followed by chicory-laced coffee and returned to the hotel early for a good night’s sleep.

‡

* * *

35 Also called Gare de Rouen, Gare Rue Verte.

36 Sicherheit = Security; Dienst = service, duty; sicher = sure, certain, secure.

37 Hamlet was one of Philippe’s cover names and his sub-circuit in Le Havre. Salesman operated in Rouen and surrounds.

38 Epouvantable = dreadful.

7

Finding and Meeting

Madame Desvaux

Tuesday 11 April 1944

Next morning, Madame Thivier provided a breakfast of steaming chic

ory-rich coffee, bread and jam. The coffee available in the shops was what was termed café national and it was better to be unaware of what its infamous mix might be. The bread was freshly baked but with ersatz flour that made the bread dark and lumpy. It was unceremoniously known as pain caca or ‘poo bread’,39 but the taste was disguised by the patronne’s plentiful homemade confiture aux groseilles, jam made from the gooseberries grown in the hotel courtyard.

As Violette walked out onto the street, doubt hit her, mixed with fear of the unknown. She was in an unknown town looking for unknown people under the watchful eye of unknown enemies. That nice French woman with her son walking beside her – was she enemy or friend? Keeping her nerve, she forced her panic back down. Wise to be careful, she told herself, make sure you’re not followed, but otherwise get on with your plan for the day.

In London, she had studied Rouen in detail on Buckmaster’s acquired maps, brought back by people already doing dangerous work in this area, and aerial maps taken from bombers and spy planes. In fact, she remembered that a certain Albert Pognant had sent across a bulky pack of up-to-date route and topographical maps, current identity and ration cards. New sets of cards had been cleverly forged from dozens of originals and given to people like her, in her case four for her own use and a few sets to pass on to others.

Violette had memorised the list of people with whom Philippe had worked. She also knew from Philippe how untrained and partially trained French men and women had already been of great service to the Allied effort and their own country, stealing coupons and identity cards, performing sabotage, garnering information on troop movements and passing it on to the Allies through Philippe and other agents.

She just had to take her time, Violette told herself, and be very, very careful. She must continue to look like a happy young woman going about her daily affairs while remaining ever watchful. She had learned well at Beaulieu in England how to check whether she was being followed and how to lose any such tails. As trainees, she and Cyril Watney, a wireless operator, were never caught. On the other hand, they caught all the trainees they tailed, except one, their friend Jacques Poirier, a Frenchman, who would take over Harry Peulevé’s Author circuit in the Corrèze after Harry’s arrest. The best thing was to think of all this as a training exercise and, in that way, keep fear and anxiety locked away.

As Paul Emile, a friend as well as an intelligence officer who had been her class instructor on the German military and security services, once told her: ‘Do the thing you most fear to do and that is the almost certain death of fear.’ Each decision she would take over the next few weeks would, indeed, be the thing she most feared to do. His phrase would come back to encourage her many times over the following months and would help her each step of her perilous way.

‡

Violette’s tenseness began to evaporate as she put her thinking processes into gear. She needed a bicycle and knew that most of the garages renting bikes were on the rive gauche so she would need to cross one of the bridges guarded by the military. That should not be too much of a problem as her papers were excellent forgeries. It also gave her an excuse for walking around the city and also past where Madame Desvaux lived, whom she thought perhaps she should visit first, and walking thus get a feel for the area. It would probably take more than one foray to find one of the two garages used as a storage dump for weapons and ancillary materials. These supplies had been parachuted into the region by London for Philippe, Bob Maloubier or the reception committees to collect and hide until the Allies invaded, or to be deployed in various sabotage exercises to weaken German defences and plans. Georges Philippon, known as Jo, had hidden away a substantial cache of weapons over the last year for Philippe and for the very secret network of which Jo was an external member. Violette would soon discover this group was called Les Diables Noirs – the Black Devils – established not too far from Ry, some thirty kilometres north-east of Rouen. One of the most secretive groups in the operation, the Diables Noirs had been set up not long after the beginning of the Occupation, formed to receive the first parachute drops of material and to gather intelligence, and later expanded to train young réfractaires40 as fighting units in the Maquis. Still today, few in France – and certainly not elsewhere – know of its existence and the great work its members did, and continued to do even after they were very nearly destroyed.

Deep in thought, Violette was suddenly halted by a German soldier: ‘Ausweis, bitte!’

She was shocked to the core by the bark of the order. She managed to utter, ‘Tenez, voilà,’ as she moved away from the kerb and handed over her forged identity papers in the name of Corinne Leroy.

‘In Ordnung! And where exactly are you going?’

‘I-I’m looking for a bike to hire,’ she replied with a frown of worry and anger. She instinctively acted like a young French women properly incensed at being questioned in the street.

‘Ah, and why might that be, mademoiselle?’ asked the German, eyeing her up and down appreciatively. Asking questions to keep a pretty thing close for a few minutes was not an uncommon activity to relieve the daily tedium.

‘So that I can try and find a relative who might still be here or might have been killed in one of the raids by the damned British.’ Said with evident annoyance.

‘Oh? Where does he come from, mademoiselle?’

‘From Lille, and hasn’t been heard of for three months and his family, knowing I live in Le Havre and had permission to visit Rouen, asked me if I would look for him. Of course I said yes, especially as I was coming through Rouen after my visit to an aunt in Paris for Easter,’ she replied somewhat sharply.

‘Very well, be careful not to buy anything on the black market. The punishments are grave.’

‘Yes, sir. Of course not. Merci et bonjour.’ She hurried on, heart thumping, nerves jangling. Yet, a small, contained feeling of satisfaction coursed through her that she had fooled another Jerry soldier. She had learned at SOE school to keep everything as close to the truth (cover story truth, at least) as possible to help avoid mistakes.

It was quite possible, Violette thought to herself as she walked on, that she would be stopped and questioned again. After all, Rouen was quite a small town.

‡

Violette walked slowly down to the quay, recalling maps, photos and aerial photos she had painstakingly memorised, and comparing them with this damaged city; bomb craters all around, dust and rubble covering thousands of square metres of this ancient town. Most was from a raid carried out in 1940 by the Germans before they marched from the north down Route de Neufchâtel into rue de la République. In response, the French had launched resistance from the rive gauche after setting fire to the town’s vital supplies of oil, destroying bridges and scuttling boats and barges. The German military soon vanquished the French and took over a town of rubble and pain. They had refrained from bombing the beautiful Gothic cathedral under what was rumoured to be a direct order from Hitler. The enemy generally behaved themselves over the first two years: they were professional soldiers of the Wehrmacht, proud of their soldiering discipline and fighting capacity; theirs would be a benevolent and disciplined occupation of territories conquered. These were not the vicious SS Panzer divisions that had massacred their way through Poland, Czechoslovakia and Russia.

From the promenade, Violette crossed over to walk along rue Jeanne d’Arc. Sections of this area were relatively intact but she found more devastation. However it was less damaged than the formless, vague terrain strewn with rubble sloping down towards the Seine that she had just left. She had seen that the Halle aux Toiles – within view of her hotel and just a few lanes to the north – was in ruins, but had not realised the devastation beyond, towards the west and the city centre. She would cross one of the temporary pontoons, vital arteries across the Seine, not merely for workers, including forced labour, but for German supplies, tanks, guns, soldiers and civilians.

First, she decided before venturing over the bridge to find a bike and thus con

firm her cover story, she would check out the fate of Madame Desvaux. She had discussed it with Philippe and they had decided this could well be her first step. It seemed only logical to try and find Madame Desvaux’s house. This woman had been an independent dressmaker. From July 1943 until February 1944 she had sheltered the wireless operator, Captain Isidore Newman, known here in Rouen, as Pierre Jacques Nerrault. As Philippe’s trusted wireless operator he had remained in the Seine area of Normandy after Philippe’s recall to London about two months before Violette’s arrival.

When the Salesman circuit was blown, Isidore was captured and interrogated. His radio was with Broni,41 his ‘bodyguard’ as Philippe referred to the Pole, who needed it to transmit for the Diables Noirs. Isidore decided there was no point in not giving all his radio keys to the interrogators as they would be of no further use to London or anyone else since he was certain Broni would warn London immediately. So now the Germans would not be able to use Isidore’s specific codes and checks; even Broni could not use them for his own transmissions. As a result there was no point in torturing Isidore, but he was imprisoned about a month before Violette arrived in Rouen. Violette thought that she just might get to talk to Madame Desvaux and gambled that the woman would not hand her over to the enemy. It was said that she was very pro-Allies. Violette hoped, too, that with her Morse code training, she would be able to use the wireless set with her own keys to London, if she could find out where Broni might be hiding out.

Although accustomed to the bombing raids over London, Violette was shocked to the core by the desolation of the area. Most of the houses in rue Jeanne d’Arc were still standing, but would number 12 be there? It had stood at the Quai Corneille end of the street where intensive fighting had taken place in 1940 and where bombs had fallen in the years since. As she turned into the street, she saw she was in luck – or rather, Madame Desvaux had been. At this southern end, on the right, stood the block where Madame Denise Desvaux had lived.

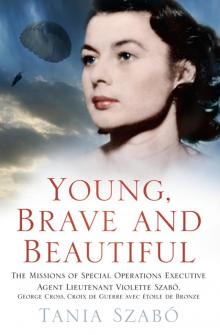

Young, Brave and Beautiful

Young, Brave and Beautiful